By Jessica Willingham

Howie Jackson was just 27 years old when he was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a form of the disease common in juvenile patients younger than 17 and adults older than 65.

But that was just the beginning of his rare and remarkable story.

Treating leukemia often involves a bone marrow stem cell transplant, which requires a viable donor who is a genetic match (usually found among the patient’s close family members). Jackson, however, was adopted from the Azores Islands, near Portugal, making a family option near impossible.

His future became a game of roulette as he was entered into the National Marrow Donor Program in hopes of finding an unrelated genetic match in time to save his life.

Almost as an afterthought, Jackson’s transplant coordinator requested permission to enter Jackson into a different kind of donor registry the National Cord Blood Program on the slim chance that stem cells harvested from the umbilical cord of a full-term pregnancy would provide the match to save Jackson’s life.

If the search yielded a match, Jackson would make history as the first adult in the state of Oklahoma to receive an umbilical cord blood stem cell transplant.

The odds were not in his favor, and it was a bet he couldn’t afford to lose.

The National Cord Blood Program is a public bank housing the umbilical cord blood of full-term pregnancies for the purpose of harvesting viable stem cells as matches for patients with blood cancers and other blood disorders, like leukemia or sickle cell anemia.

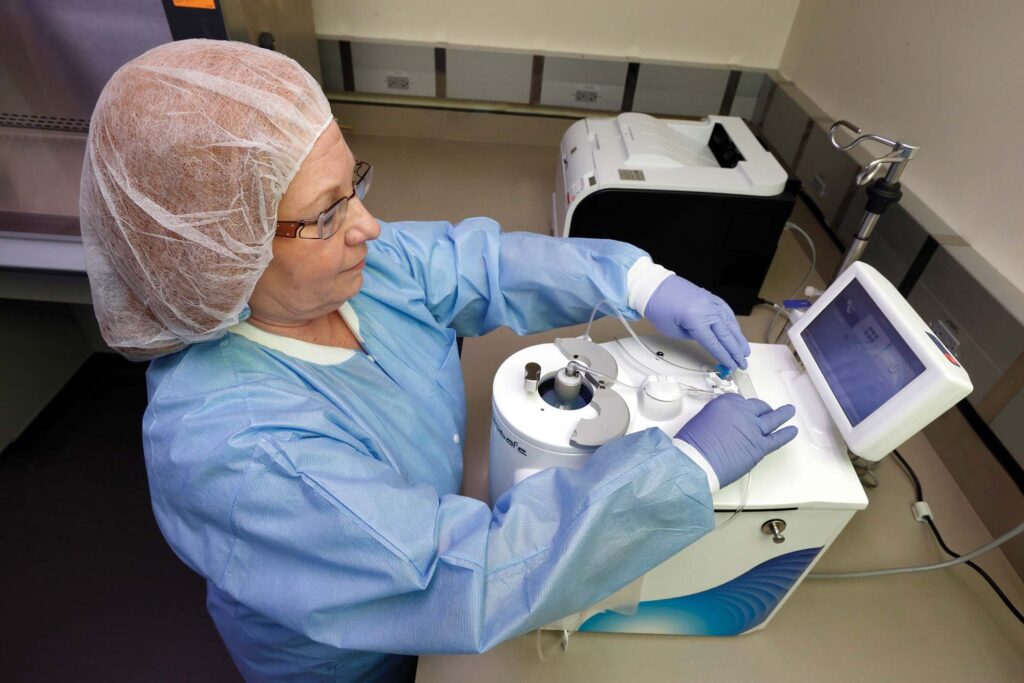

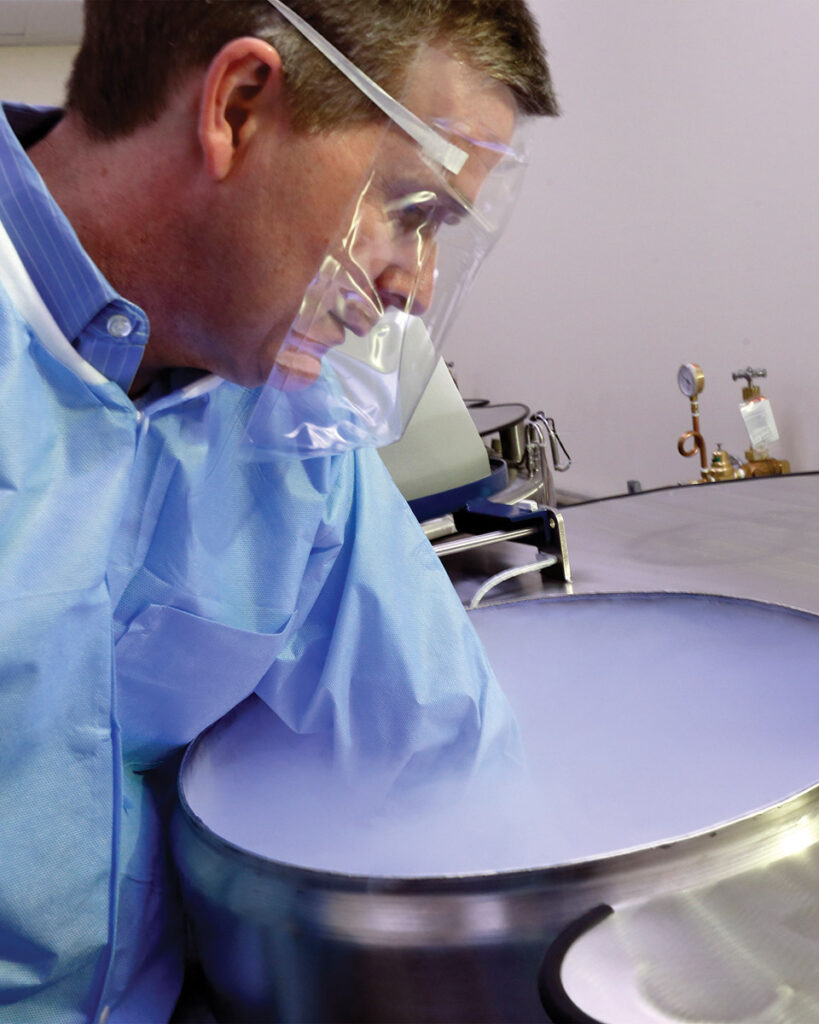

The umbilical cord is taken after childbirth without harming the child or mother. After collection, cord blood is tested for tissue type and viruses, processed for freezing, and stored until it is needed for transplantation.

Unlike private umbilical cord banks, which collect and save umbilical cords for the specific use of being a match for the individual it was harvested from or for members of the individual’s family, a public bank can be utilized by any eligible patient entered into the registry. So someone of Portuguese descent, like Jackson, could be a genetic match for a donor halfway across the country. Further, public umbilical cord banks are completely free.

“In Oklahoma, prior to our public cord blood bank, the only option for an expectant mother who wanted to utilize her baby’s umbilical cord was to bank it privately,” said Gary Lynch, director of corporate development for the Oklahoma Blood Institute (OBI). “The initial cost to bank privately is between $2,000 and $2,500, then an additional $150 a year after that. All of this without a guarantee that it would be useable for her child or an immediate family member.”

Without a public bank in Oklahoma (the closest option is in Houston, Texas), umbilical cords and the potentially lifesaving stem cells they hold were considered medical waste and thrown away. OBI wanted to change that.

The need for a public umbilical cord blood banking center within Oklahoma is as unique to the state as waving wheat and windy days. Oklahoma has the largest Native American population per capita in the United States, representing an opportunity to grow the national registry to further include and provide matches for minority patients.

“Only 0.2 percent of 1 percent of the national registry is Native American,” Lynch said. “Oklahoma’s Native American population, the largest per capita in the country, is the least represented group. We can add to the diversity of the national registry by leaps and bounds, and in a relatively short period of time.”

OBI set a goal to raise $3 million enough to establish and maintain the public umbilical cord blood banking center for two years. OBI began reaching out to organizations within the state for financial support.

The Noble Foundation reached back with $15,000 to support the center’s creation and operations. The Noble Foundation, a longtime supporter of OBI, has given $790,000 to date in support of the institute and its various missions.

“The Noble Foundation and the Oklahoma Blood Institute share the same goal of advancing Oklahoma and its quality of life,” said Mary Kate Wilson, director of philanthropy, engagement and project management at the Noble Foundation. “In addition to helping Oklahomans, the public bank gives us the opportunity to increase the diversity of the national registry and help people everywhere. We wanted to be a part of this noble cause.”

The center opened in January 2014. OBI will soon complete the rigorous Food and Drug Administration licensure process for the cord blood facility. Additionally, a major portion of OBI‘s original headquarters in Oklahoma City has been renovated to accommodate offices, laboratory and cryogenic storage tanks for the program.

OBI‘s new public umbilical cord blood banking center is one of 17 in the country and 24 worldwide. Mothers giving birth at OU Medical Center can choose to donate their child’s umbilical cord to the state bank. OBI will partner with additional hospitals in the future and eventually collect enough cords to qualify for entry in the national registry. Opening OBI‘s public umbilical cord blood bank and establishing its presence in the national registry is just the beginning; raising awareness, sustaining funding and getting mothers to donate are their greatest challenges.

“Cord blood is being used for treatment of blood disorders, but scientists are beginning trials for diabetes and traumatic brain injuries,” Lynch said. “The future is unlimited.”

Today Howie Jackson is cancer free. He was the first adult in Oklahoma to receive a stem cell transplant from umbilical cord blood after finding six perfect genetic matches in the national donor registry.

He entered into remission.

A year and a week after his successful transplant, his leukemia returned. But because his first transplant was a year earlier, he was eligible to enter the national umbilical cord blood registry again.

Five of the original six genetic matches remained available; thus, Jackson became the first adult in Oklahoma to receive two stem cell transplants from umbilical cord blood.

Because of his success, it is now common practice to use two cord units on adult patients of leukemia.

Today, Jackson often takes his story to Washington, D.C., in hopes of raising awareness and funding opportunities for the American Cancer Society and National Donor Marrow Program. Historically, the national donor program has never been fully funded.

“Our biggest hurdles are manpower, resources and getting this information out to the general public,” Jackson said. “If we keep trying and we spend enough money, we will beat cancer. That’s a promise. I am a man who was cured by God and because people gave money for research.”

The first umbilical cord blood stem cell transplant was successfully completed in France in 1988 on a child diagnosed with a rare blood disorder. The first transplant on an adult was successfully completed in 1997, just a few years before Howie Jackson’s acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosis in 2001.

Stay up to date on all the ways the Noble Foundation is helping address agricultural challenges and supporting causes that cultivate good health, support education and build stronger communities.