Students Find Hope, Confidence and Futures from Sports

Amie Stearns

on

February 25, 2025

Students Find Hope, Confidence and Futures from Sports

The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation’s grantee, Fields & Futures Foundation, builds and maintains sports fields and facilities that allow Oklahoma City Public School students to thrive in the classroom and sports.

Playing soccer, running track or cheering at a competition has always been about more than wins and losses, personal records and school titles. Students gain confidence, resilience and hope for their futures . When enough students begin to believe in themselves and their teammates, they can change their community for the better.

Tim McLaughlin met Keith Sinor, athletic director at Oklahoma City Public Schools, during a bus tour of OKCPS facilities in 2011. McLaughlin, an athlete, sports fan and Oklahoma City-based entrepreneur and philanthropist, was shocked at the state of the athletic fields and committed to doing something to help.

By 2012, Sinor and OKCPS partnered with McLaughlin’s Fields & Futures Foundation to renovate the sports facilities at one school in the district. Today, more than a decade after the partnership began, every school campus at OKCPS has benefitted from the partnership with Fields and Futures. As a result, the district reports a record 28% of students participate in athletics, double the amount from 2012. What’s more impressive are the benefits administrators are seeing in the classroom as a result.

Building Fields and Futures

Fields & Futures Foundation kicked off their work in 2012 with a sport’s complex renovation at Jefferson Middle School. The plan was initially to renovate the football and soccer fields. But quickly McLaughlin got permission to also tackle the baseball and softball fields, too.

It wasn’t long after the construction was completed that Sinor called McLaughlin out of breath and elated. The school, and surrounding streets, ran out of parking during a multi-game sporting event. Better fields lured students to participate in teams, and the community showed up on game day to support them.

The project went so well, the partnership expanded – slowly – to other campuses. At first, construction of new fields at a school happened once a year. But momentum built, and by 2024 , Fields & Futures completed the renovation phase of its mission. In total, the organization transformed 71 sports complexes across 19 school campuses.

In tandem with renovating fields, McLaughlin and the Fields & Futures team realized they couldn’t just construct new fields and facilities and walk away. McLaughlin and his board felt they had a duty to maintain the fields and buildings to ensure they didn’t become a burden on OKCPS or fall into disrepair.

“If we’re going to build it, we’re going to maintain it,” McLaughlin said to board members and donors. After a decade of focusing on funding construction of new fields, Fields & Futures turned its attention to fulfilling their field maintenance endowment.

“This is where the Noble Foundation has been so critical to this story,” said Dot Rhyne, former marketing director at Fields and Futures, of the Noble Foundation’s grants toward satisfying Fields & Future’s endowment.

Noble Foundation, moved by the long-term stewardship of the facilities and the positive impact the fields have on students’ lives, awarded Fields & Futures Foundation three grants totaling $125,000 to help them meet their $10 million endowment goal.

“The Noble Foundation is proud to support Fields & Futures in their mission to provide lasting opportunities for Oklahoma City students,” says Stacy Newman, director of philanthropy at the Noble Foundation. “Investing in these athletic fields is more than just building spaces to play—it’s about fostering resilience, confidence, and hope in young athletes who will carry these lessons far beyond the game.”

A Team for Every Student

Team sports, while a wonderful asset to teach soft skills to students, can also be an intimidating place for a student who doesn’t see themselves as an athlete. Mandi Dotson has experienced that kind of resistance when recruiting students to join cheerleading.

Dotson is the operations manager at Fields and Futures Foundation, and, more recently, the director of cheer. She stepped into the latter role in 2015 after finding out cheer hadn’t before been considered a school-sponsored sport at OKCPS.

“I got a meeting with the athletic director immediately,” says Dotson. “He confirmed, cheer’s never been under the umbrella of athletics in the district.”

Dotson made her case, and without hesitation, OKCPS agreed – cheer should be a funded athletic program. That decision opened up an opportunity for more students to find a home on a sports team.

“Coming in blind [to cheerleading] is ok. Students don’t have to be the best athletes to come cheer at Oklahoma City Public Schools,” says Dotson. “This is open for everyone, to all types of kids, men and women.”

Her openness to all students, regardless of their previous experience with the sport, is what helps draw students out for tryouts. In the first year of the cheer program at OKCPS, Dotson organized a single-day cheer camp to introduce students to the world of cheerleading. In the first year, 150 students attended. Last year, in 2024, Dotson expanded the camp to three days and hosted 330 student athletes. In her eyes, those are students who didn’t previously fit into an existing OKCPS sport.

“Our mission has always been to inspire kids to play sports,” explains Dotson of Fields and Future’s focus. “Cheerleading became another avenue to get more kids on more teams. And it’s been huge! I mean 330 kids weren’t on a team because there was no cheerleading before.”

Cheer is now one of the biggest sports in the district, and it’s impacting students in tangible ways. Including inspiring them to attend college through athletic scholarships.

This past December, Fields & Futures partnered with Impact Xtreme, an Oklahoma City-based youth cheer squad, to host their first cheerleading combine, an event where students can showcase their talents in front of college recruiters and coaches. Those in the audience included staff from nearby institutions like University of Central Oklahoma, Oklahoma Wesylan University, Southwestern Christian University, Oklahoma Baptist University, Southern Nazarene and Oklahoma’s only historically black college and university (HBCU), Langston University.

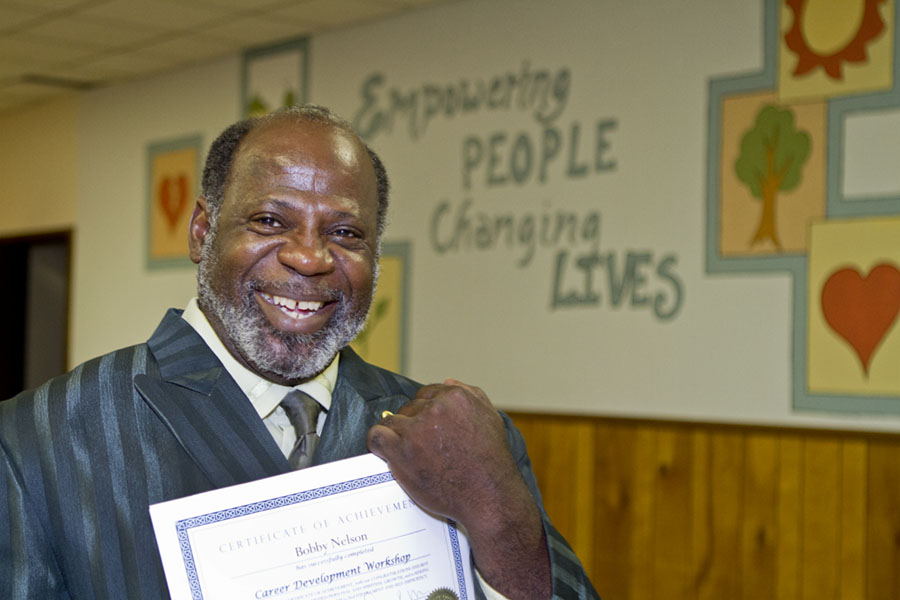

“Every single OKCPS kid who showed up left with some kind of scholarship offer. There were 40 athletes, and all of them got an offer to cheer at the college level,” recalls Dotson. “These are these are kids that didn’t know [attending college] was even a possibility.”

Investing in Athletes and Academics

Using sport as an avenue to better support and inspire historically underserved youth is not a new concept to David McLeod. He’s a former youth athlete and current Interim Director of the School of Social Work at Oklahoma University. He’s also working with Fields and Futures to help tell the story of OKPCS student athletics through data.

McLeod is a psychopathologist by degree and has spent his career as a researcher, educator and a mental health professional studying mental illness and distress and the conditions that can result from them.

As part of the collaboration with OKCPS, Fields and Futures Foundation wanted a way to quantify the impact athletics had on students. Administrators at OKCPS shared more than 21,000 records with McLeod. The data is aggregated, and represents students in grades 5 through 12, both athletes and non-athletes.

Among the numbers and statistics, McLeod found evidence to reflect the truth McLaughlin knew from the start: there is a strong connection between sports participation, academic success and long-term wellness outcomes.

McLeod says OKCPS student-athletes perform better in the classroom and achieve better outcomes after graduation than their non-athlete peers. In a district struggling with chronic absenteeism, student-athletes attend 22 more days of school per year than their peers. Which he says may contribute to their 8% higher grade point averages.

“A D-grade keeps them off the team until they can get their grade back up,” explains former marketing director, Dot Rhyne. “Coaches in the early years were excited because they finally had enough kids out for the team that they had to establish academic standards and bench kids who needed to focus their energy on class work.”

OKCPS student-athletes are also more likely to enroll in honors or advanced placement classes and participate in concurrent college courses. Graduation rates among student-athletes also tend to be higher nationally. McLeod found that OKCPS student-athletes graduate 90% of the time, a significant uptick from the 65 to 70% average for non-student athletes.

To take his research further, McLeod coupled the OKCPS student record data with focus groups and conversations with students. He’s been able to link sports participation with long-term, beneficial outcomes for students.

“We know we have high-trauma kids, urban core kids. A lot of them have jobs, family responsibilities, transportation challenges. They have all kinds of stuff going on. But in that large data set, we saw statistically significant findings that these student-athletes have a higher resilience to adversity.”

The data suggests OKCPS student-athletes are 20% more resilient than their peers when it comes to handling personal and academic challenges. They’re also less likely to experience emotional problems – more so among female students, which McLeod attributes to the relationships students build with their teammates.

“One of the things that our brains will do, especially in adolescent brains, is think about the consequences for their teammates before they think about consequences for themselves. So, when they have those team bonds and people that are depending on them, we’ve created a sense of surrogate family.”

Compared to their peers, and national averages, the student-athletes at OKCPS worry less, show less anger and nervousness, and are less distracted. The data set also showed a link between participation in sports and an increase in positive behavioral choices.

Student-athletes have a support network – teammates and a coach they can rely on. Friends they trust and a trusted adult who isn’t a parent or primary caretaker are two valuable benevolent childhood experiences, or BCEs. Evidence shows that BCEs are associated with lower trauma-related symptoms and can be capable of counteracting negative impacts of childhood trauma.

According to the OKCPS data, participation in sports provides many benevolent experiences for students.

“The average student-athlete that we surveyed reported a 9 out of 10 BCEs that they’ve personally experienced through sport participation,” says McLeod. Adding other factors that sports bring to students, such as a predictable daily routine, enjoying school and opportunities to engage in play.

McLeod emphasized how important those findings are for students, suggesting the positive effects can last students into adulthood. But he is most excited about what the students said when asked about their hope.

He explained the science behind hope – it’s not simply a wish. Hope is to believe that tomorrow can be better, and an individual feels they have a path to get there.

“Increasing belief and personal agency are an important part, but also increasing direct, tangible, realistic ways to get it done,” McLeod said. “We found that kids who participate in sports tend to have higher levels of hope. We know that hope is a great predictor of wellness and life success as well.” Those who participated in sports in school, or as adults, can relate to the beneficial experiences. But for students in the urban center of Oklahoma City, sports can be life changing. Fields and Futures Foundation knew they needed to take action. Their founders understood the importance of sports for youth. What they may not have known at the time is the tremendous benefits their fields and facilities provide for students off-campus.

Noble Foundation News

Stay up to date on all the ways the Noble Foundation is helping address agricultural challenges and supporting causes that cultivate good health, support education and build stronger communities.