By Courtney Leeper

Less than 35 words make up the body of one of the first letters between the Noble Foundation and Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

The brief note dates back to July 10, 1970, and it enclosed a $25 donation. The donation, which amounts to about $155 in today’s value, was sent by John March, Noble Foundation president at the time, in response to a request for $25 to help fund the Leonard P. Eliel Lectureship for Endocrinology.

“We hope this will serve in a small way to aid in the success of the lecture series,” wrote March, who had joined OMRF‘s governing board just two months prior.

Forty-five years later, the letter is filed away in the back of a bulky, pale green folder one of five dedicated to The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation at the medical research institute in Oklahoma City. Though short and simple, the letter marks the beginnings of one of the Noble Foundation’s longest tenured granting relationships.

Since 1977, the Noble Foundation trustees have awarded OMRF more than $19 million to support their researchers’ work in studying ways to fight human disease. The most recent and largest of the gifts was $6 million to support the construction of the Research Tower, which houses The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation Cardiovascular Institute.

“The Noble Foundation trustees view OMRF as a premier medical research center,” said Mary Kate Wilson, director of philanthropy, engagement and project management. “It brings a certain synergy of research to Oklahoma and increases our state’s profile in terms of benefits to healthcare. They are more of a partner rather than simply a grant recipient.”

In 1946, OMRF was incorporated by a group of University of Oklahoma Medical School alums. The first research building was dedicated in 1950, and the next two decades of research increased the organization’s credibility through discoveries related to cancer, cardiovascular disease and other debilitating health conditions.

By the mid-1970s, the need for more research space was growing dire. In 1977, the Noble Foundation awarded its first substantial gift to OMRF $500,000 to enlarge and centralize the Laboratory Animal Resource Center. In the early ’80s, OMRF called upon the Noble Foundation for further help. William G. Thurman, M.D. OMRF president, announced the construction date for a cardiovascular research building that would provide 30,000 additional square feet of research space. Before construction could begin, at least 60 percent of the required funds had to be in OMRF‘s hands. This was especially challenging because of the economic climate of the day the 1980s oil bust had spiraled Oklahoma into a devastating recession.

Despite the trying financial times, the Noble Foundation trustees recognized the need for high quality cardiovascular research. In early 1950, Lloyd Noble chaired a fund drive for the Oklahoma Heart Association. In a letter requesting donations, he wrote: “Heart disease is your business and my business, because you, your family and friends are among its potential victims. No one can say with any real assurance, ‘this can’t happen to me’.”

A few days later, on Feb. 14, he unexpectedly died of a heart attack.

John Snodgrass had assumed the leadership of the Noble Foundation when the trustees approved $500,000 to be given to OMRF for the cardiovascular research building, which was later named the Acree-Woodworth Cardiovascular Research Building. Snodgrass spoke of Noble’s dedication to service and giving during the building dedication on Sept. 23, 1983, 38 years to the week after Noble founded the Noble Foundation.

He also announced that the trustees wanted to do more than just contribute to the building. In memory of Noble, they established the Lloyd Noble Chair in Cardiovascular Research, a permanent $1 million endowment, and set aside $1.5 million for cardiovascular research operating support over the next five years.

“Although Lloyd Noble’s original gift to the Noble Foundation and his subsequent bequests were substantial, I doubt that even he visualized the size and scope of the good works that he had made possible for mankind,” Snodgrass said during the dedication.

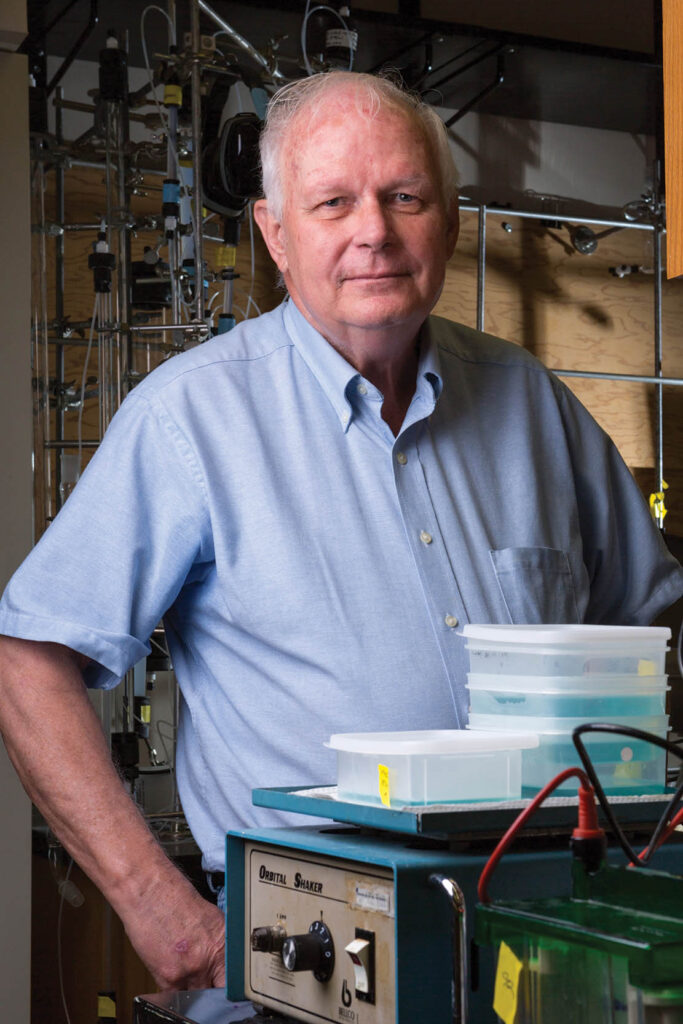

Across from OMRF is the University of Oklahoma College of Health Building. That’s where Charles Esmon, Ph.D., started his first laboratory after finishing his postdoctoral work at the University of Wisconsin in the mid-1970s.

In the summer of 1982, Esmon joined the OMRF scientific staff and moved his lab into the not-quite-complete Acree-Woodworth Cardiovascular Research Building. The promise it offered was too tempting more space to conduct his research.

In September 2015, Esmon sat in his office just down the hall from the connected cardiovascular research building in its mirror image, The Massman Building and Mary K. Chapman Center for Cancer Research, which was also constructed with Noble Foundation support.

It was a typical Oklahoma summer hot, Esmon recalled. His eyes seemed to search for the past, and he chuckled in remembering it. They rolled their equipment over to the new building in the heat trying not to break anything, he said.

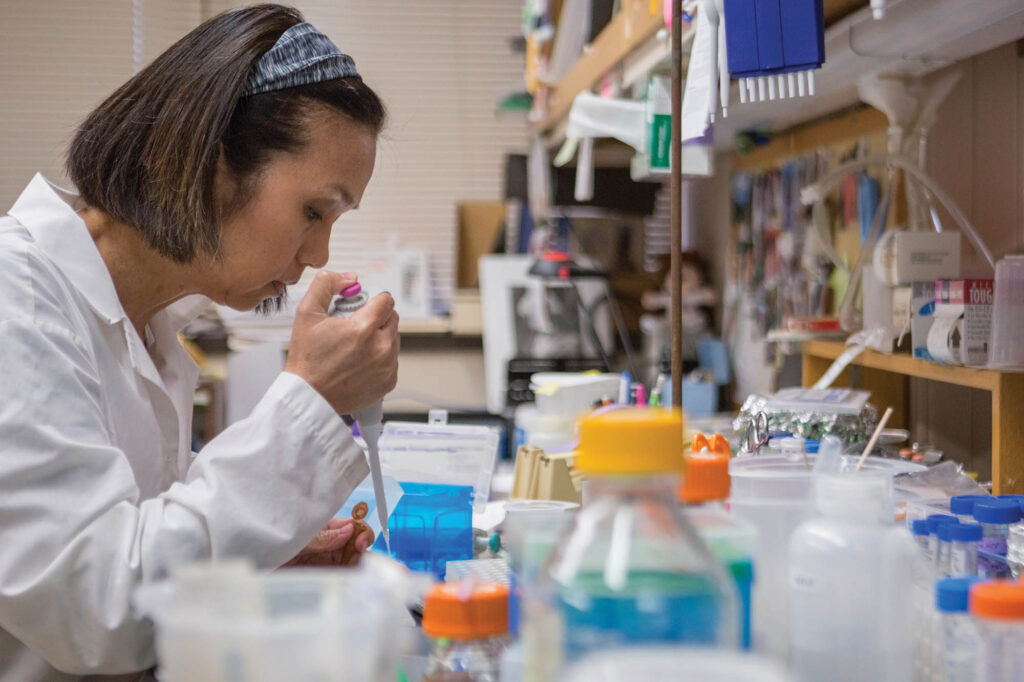

Once they moved in, the building was alive with research nearly 24-7. At one time, one lab member started his day at 10 p.m. and worked through the night in order to have everything prepared for the next day’s experimentation.

Esmon’s lab was, and still is, studying blood and how it clots. Early in his research career, Esmon began studying Protein C, a critical component of blood that prevents it from clotting within the body. One of the benefits of the new lab was a whole room dedicated to the messy process of isolating Protein C from blood cow blood.

It was Oklahoma’s vibrant livestock industry, in part, that had drawn Esmon to the state. Oklahoma City’s beef packing plants kept him supplied with the important research material, which ultimately led his lab to discoveries fundamental to two life-saving therapies: one for a deadly genetic Protein C deficiency; the other for sepsis, a serious illness caused by infection in the blood. The work is also the basis of other research focused on a host of major diseases, from heart and blood diseases to cancer and diabetes.

Over the years, Esmon’s work has earned him many high profile recognitions. He became Oklahoma’s first Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator in 1988, and he has received multiple awards from the American Heart Association, the American Society of Hematology, and the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis. In 2002, he was elected to the prestigious National Academy of Sciences.

While agriculture in a way supported his early research, his research is also supported by the Noble Foundation a research organization dedicated to supporting agriculture. In 1996, Esmon was honored as the first Lloyd Noble Chair in Cardiovascular Research, a position he continues to hold.

For Esmon, having the Noble Foundation’s financial support means stability for his lab and not having to rely on short-term governmental grants.

“Even in the best circumstances, you can get only 75 percent of your funding from grants,” said Stephen Prescott, M.D., OMRF president. “Financial supporters like the Noble Foundation are one of the reasons we’ve been successful as an organization. Historically, if we’ve had a worthy project, the Noble Foundation has been willing to help us.”

Without relying on short-term grants, Esmon has been able to cultivate his lab members, helping them be successful over time. This, he said, has helped him maintain some laboratory members for more than 20 years.

“The Noble Foundation provides tremendous support,” Esmon said. “Because of them, I can take a longer-term view of research with the people in my lab. That simply would not happen on short-term grants.”

At 68 years of age, Esmon continues to build off initial findings. About five years ago, Esmon’s lab discovered a new property of the critical proteins called histones. These proteins are responsible for folding DNA so that it fits inside the cell nucleus. Although histones serve this critical function, when they exit the cell, generally through a traumatic experience like a car accident or gun shot, “They control your demise,” Esmon said. His lab’s current research focuses on using this knowledge to help trauma victims. The research is also instrumental in an experimental treatment for hemophilia being developed.

In the spirit of Lloyd Noble, Esmon said he chose to study blood coagulation because he’d be able to ask interesting basic questions that are relevant to making life better for people.

“The research we’re studying affects all the major killers heart disease, sepsis, cancer,” Esmon said. “You might develop a reagent, test it, then the next thing you know you’ve got a therapy that saves lives. That’s rewarding. That’s what I’m here to do.”

Stay up to date on all the ways the Noble Foundation is helping address agricultural challenges and supporting causes that cultivate good health, support education and build stronger communities.